A Republic, If We Can Keep It

Core questions on tech, geopolitics, and philosophy

Many say the US is at a key moment in the race to technological supremacy with China. How do you frame our position now?

The US has the best models and compute. We’re ahead… but China’s lag is measured in months, not years.

America is still the “R&D lab of the world,” as Alec Stapp of the Institute for Progress often puts it. The US hosts about 75% of global frontier AI compute - the chips needed to make leading AI models. We have a great innovation ecosystem, the world’s largest economy, and a strong first-mover advantage.

But we face headwinds — lack of Congressional leadership in AI, a self-sabotaging global trade war, a rejection of the high-skilled immigration we need to build new chips and AI systems in America, and clumsy, partial state ownership of firms like Intel. Major AI players also face a bevy of cybsersecurity issues, which my colleague Elsie Jang recently wrote about in fine detail.

But China remains the world’s factory. It really succeeds as a “fast-follower,” though it is not limited to that role. Chinese technologists are making their own original, frontier advances. DeepSeek is evidence of that. China is also making great strides in robotics and autonomous manufacturing systems.

There is such a thing as a “second-mover advantage” — you go first, and I’ll learn from your mistakes. The People’s Republic of China made massive investments in critical infrastructure, rare-earth minerals, and is growing its own domestic chip production ecosystem. They are the world’s top manufacturing hub, literally building the future at “breakneck” speed, as Dan Wang writes.

But China faces the usual authoritarian headwinds — lack of openness, rigidity, censorship, repression, and the aftermath of Xi Jinping’s crackdown on the tech sector. They are also struggling to gain access to frontier AI compute — the chips needed to build advanced AI systems. US and allied export controls have hit China’s burgeoning advanced chip industry hard, and it will likely take years to make up for this setback.

The AI race between the US and China is challenging to navigate as a classical liberal. How do you balance a love of market competition with national security concerns amid an increasingly antagonistic US-China relationship?

One of my classical-liberal guiding lights is the father of economics, Adam Smith. He argued in The Wealth of Nations that “defence… is of much more importance than opulence.” I tend to agree with that. Basic security is essential if people and markets are to flourish and grow securely.

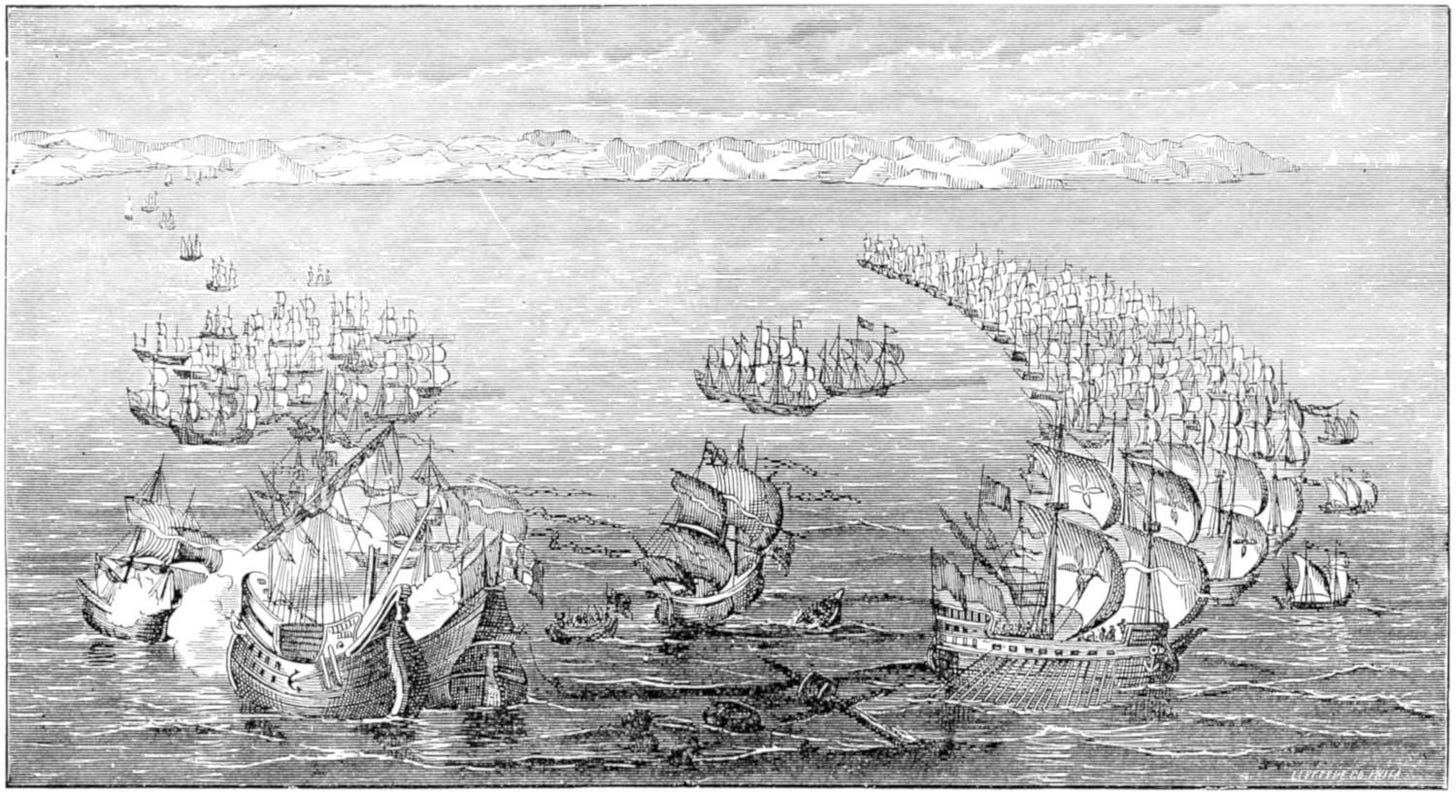

Smith actually made this statement in his defense of the Navigation Acts, which limited the use of foreign ships so that Great Britain could establish a vibrant merchant marine. His point — and mine — isn’t that the state should pick winners and losers and centrally plan the domestic economy all in the name of a vague appeal to national security. Rather, the state’s duty is to literally — physically — defend the realm from foreign aggression. Not much else can happen if that is not achieved reasonably.

Smith probably remembered the failed Spanish Armada that sought to invade England in 1588 — an invasion the English navy repelled with superior, longer-range cannons against Spanish galleons prepared only for short-range combat. Today, the US has to contend with other dark storms on the horizon that threaten the metaphorical (and literal) harbors and sea lanes of our commercial republic — disturbing realities like nuclear weapons, autonomous systems, drones, bioweapons, cyberwarfare, and hypersonic missiles.

John Stuart Mill also makes the point in his classic work On Liberty that a people must be free collectively from foreign rule before they can be free individually. Now, I don’t know about the sequence, empirically, but I do know that freedom requires security from coercion both domestically and internationally, from internal and external threats alike. All of us are engaged in a struggle to achieve that freedom, which must be renewed and can always be snatched away if we get distracted and become fundamentally unserious.

The best defense for our commercial republic is the maintenance of a free-market system and the moral ecology that must undergird it. Commerce gives us the edge, and virtue makes our commercial society work for the common good.

Why do we need democratic values in frontier AI models and innovation more broadly?

Technology of all sorts shapes and is shaped by our intent, by our values. If America and its allies can get more models of democratic origin out into the global market, we can help create and reinforce digital spaces and social norms that encourage freedom and human flourishing. Open-source models are one major, critical vector for this task, especially globally.

AI will likely only grow in importance and influence. As it becomes more agentic, it is imperative to have it grounded in the liberal-democratic values we hold most dear, the same ones that made America great in the first place.

Do we want to rely on robots that must ultimately report to Chinese Communist Party cadres? I think our first presidents — Washington, Adams, Jefferson, and Madison — would all be quite disturbed by that idea.

America, despite all its flaws, has been a tremendous force for creating greater wealth and better security in the world. Our economic and technological position helped us secure that.

There’s a wide spectrum of forecasts on AI development. Between “doomers” and 20% productivity growth, where do you fall?

Well, you can be a doomer and believe in 20% productivity growth quite easily! But I think I know what you’re getting at…

Yogi Berra, the legendary New York Yankees coach, once said that “It’s tough to make predictions, especially about the future.” Where we’re heading is radically uncertain. We could see AI meet headwinds in development, diffusion, and regulation that greatly slow it down. But tech development can be quite fast, especially if AI begins to develop its own capabilities in a self-perpetuating cycle. This time really might be different.

But diffusion — the process whereby a technology spreads throughout the workforce and population — can be slow going. That’s because social systems at the macroscale are much slower to adapt to radical innovations. AI might break this trend, but it could also run afoul of the same human sluggishness that stymied past technological breakthroughs.

I’m not an economist, so I tend to adjust my own forecast to those who better understand macroeconomic models.

Tyler Cowen is one of these economists, and he’s gone on the record “suggesting that AI will boost economic growth rates by half a percentage point a year,” which he says “is very much a guess.” But, “It does mean that, with compounding, the world is very different a few decades out.”

US GDP has grown about 2.5% each year for the last decade. Tyler’s forecast bumps that up 50 basis points to 3% a year. Over a decade, that compounds to 5% growth in US GDP, which is ~$1.5T.

That’s like adding the economy of Spain — or with a bit extra oomph — even South Korea. And in ten years — that’s incredible! And say the whole world is also getting that reinvigorated growth? That would be quite powerful.

The doomer case, however, might occur even with all this growth. Maybe AI will make it harder to work and create things as imperfect, autonomous humans? Maybe we will irreparably farm out our decision-making to these systems? Maybe states will use AI to surveil and enslave their populations? We should take these scenarios quite seriously.

I think we can manage them, however, and that we should not overreact to the more imaginative and speculative scenarios, which are typically built on a series of medium to low probability assumptions that necessarily, through combinatorics, drive the overall probability down to near-zero.

But yes, stay frosty! Update your OODA loop. Plan to adapt.

Many in the tech community have described a utopia created by AI. Why do you believe not only is that impossible but dangerous to try and achieve?

I think the historical record strongly suggests utopian movements are generally failures and terrible plights on humanity.

There’s something about believing your political action alone can bring about earthly paradise that leads you to act like a menace and do whatever the hell you want because you believe you’re leading everyone to nirvana. Or perhaps that is the rhetorical cover for more base motives. Bootleggers and Baptists alike have much to gain from this kind of strategy.

Regardless, hard cases make bad law. We should build in a way that makes us resilient, decentralized, and antifragile so we can “improvise, adapt, and overcome.” That’s the American way, and we should stick to it. But only if we keep our heads… and our values.

Many thanks to Dallas Floer, Sam Alburger, Kim Hemsley, and Rebecca Lowe for arranging this interview and providing feedback.