A Patchwork Scorned

Congress’s troubled prelude to the AI Action Plan

The White House’s new AI strategy is here. The plan offers a (mostly) promising array of policy options for the US Federal Government to pursue as it looks to accelerate innovation, build infrastructure, and lead internationally.

Notably, however, Congress is not exactly front-and-center in the new strategy. That makes sense, given the unrelenting demosclerosis that’s spread throughout the Hill and pretty much every government institution in Washington. Something’s got to give. And for a brief period in June 2025, it seemed like that something might come by way of a federal AI “moratorium” on state laws regulating AI systems.

House Republicans on the Energy & Commerce Committee introduced the moratorium on May 14th, and the Senate Parliamentarian affirmed its inclusion in the One Big Beautiful Bill Act on June 21st. Following stiff opposition from GOP senators and concerned governors, the Senate voted to strip the moratorium from the bill. It died on July 1st, having lived just 48 days — about the length of time it takes a basil seed to grow into a mature plant.

So… what was all that about, exactly? And what can we expect for AI governance in the US in the days to come? To answer these questions, I caught up with Lauren Wagner and Matt Mittelsteadt to get a postmortem on the very mortal moratorium. Matt is a Technology Policy Research Fellow at the Cato Institute, and Lauren is a Fellow at the Abundance Institute and an Advisor to the ARC Prize Foundation.

In our convo — part one in a two-part series — we discuss the coalitional dynamics at the root of the failure, what it means for Big Tech and Little Tech in the US, and how the AI Action Plan can still bolster American AI — with or without Congress.

Concepts of a Plan

Ryan Hauser: What’s your assessment of the White House’s new AI strategy, and how does the moratorium failure fit into that? Does this make major federal AI legislation even less likely? The new AI strategy has a lot of merit, but it also seems like the White House is tacitly acknowledging it has no major plans for movement outside the executive branch.

Matt Mittelsteadt: The White House’s new AI strategy takes necessary steps to invest in, prioritize, and unleash AI innovation. Perhaps the most important provisions for Congress will be the diverse new data collection schemes. A major challenge for federal legislation has been identifying and agreeing on which problems are real and serious. Data will bring clarity that could drive greater consensus on what is needed and sow the seeds for action.

Lauren Wagner: The AI Action Plan marks a shift in strategy away from sweeping federal legislation and toward pragmatic action the executive branch can take now. Rather than waiting for Congress to pass major AI legislation, the plan focuses on building the infrastructure needed to govern AI through standards, procurement, and targeted intervention.

That may prove to be more effective. While many state-level AI bills aim to protect citizens, most struggle to keep pace with the technology or address the harms they claim to mitigate. In many cases, the relevant protections already exist under consumer, civil rights, or employment law. The AI Action Plan fills a critical federal gap — invest in building the capacity to understand AI systems before regulating them at scale.

That includes efforts to improve interpretability, control, and robustness, and to build an AI evaluations ecosystem to track model performance and risk across contexts. It supports open-source development, enabling external research and scrutiny. And it targets federal investment in domains where public-sector leadership is critical: biosecurity, national defense, and synthetic media.

Crucially, the strategy also recognizes that regulation isn’t the only tool for shaping AI development (which I’ve written about at length). Today, the most widely used AI procurement standards, such as NIST’s AI Risk Management Framework and OECD guidelines, are voluntary, yet they shape purchasing decisions across both government and industry. Billions of dollars in public and private sector contracts are awarded based on adherence to these standards. By anchoring the Action Plan in federal procurement, the administration is creating strong market incentives for safer, more transparent systems.

Could you give some examples? How does the new AI strategy use procurement to provide regulatory guidance?

One example: the plan calls for a federal AI incident response program to log real-world failures and risks. Over time, insights from that repository could inform procurement guidance issued by the Office of Management and Budget (OMB). Companies hoping to sell into government, and the enterprise sector more broadly, will need to demonstrate how they mitigate and report those risks.

The plan also includes language directing agencies to consider a state’s AI regulatory climate when awarding discretionary funding. That provision signals that poorly designed or overly restrictive state regimes may come with tradeoffs. Its practical effect remains to be seen, but the intent is clear: governance is moving through standards, incentives, and institutional capacity, not just through laws.

In short, the AI Action Plan lays critical groundwork. It won’t replace the need for future legislation, but it builds the foundation for more informed, effective governance. As always, the challenge will be execution.

Moratorium Redux

Ryan Hauser: A lot of the legislative action on the moratorium proposal really came down to a two-week period or so. What’s your synopsis of the events? How did it affect your daily work?

Matt Mittelsteadt: Yeah, from my perspective, this really caught me off guard, to be honest. I’m sure other people who were involved in the actual crafting of the One Big Beautiful Bill Act had further details on how the sausage got made. But when the House introduced its bill, I think a lot of people in the AI policy community, including myself, were very surprised to see not just something this significant but specifically something along the lines of a moratorium on state AI regulation. This was something that a lot of people thought was a pipe dream in terms of regulatory possibility — definitely not something people imagined would actually end up passing the House, as we did see.

Now, naturally, what happened next after that initial surprise? There was a bit of a time delay as the senators took a keen look at what the House had put forward. But what immediately followed was a ton of revisions. One of the big challenges with the original version of the bill passed by the House was that — to comply with various arcane Senate rules — you can’t just pass through this reconciliation process a straight-up moratorium on what states can and cannot do. Everything had to be attached to some sort of budgetary provision. It had to be related to the dollars and cents the US government is putting out.

When this hit the Senate, what happened next was a lot of revisions to try and figure out how to bake this into the budget in some way. How can they attach this to some sort of pot of money? We saw a couple of different iterations of that, which were mostly related to broadband funds. And in that, there were a lot of complications in the politics. Some states were more married to those broadband funds and didn’t want strings attached to them. There were also certain fights around what carve-outs existed in this bill.

The House had one plan. The Senate introduced another. Then the Senate introduced several other revisions on carve-outs, including adding things like carve-outs for child safety legislation and IP. We saw a lot of different iterations trying to appease a bunch of people, trying to connect provisions to budget rules. At the end of the day, the complexity of the process in part did lead to its ultimate demise. It also made it very difficult to analyze, in real time, what this thing even was supposed to do or would do ultimately. That was one of the big anxieties that may have contributed to its ultimate failure.

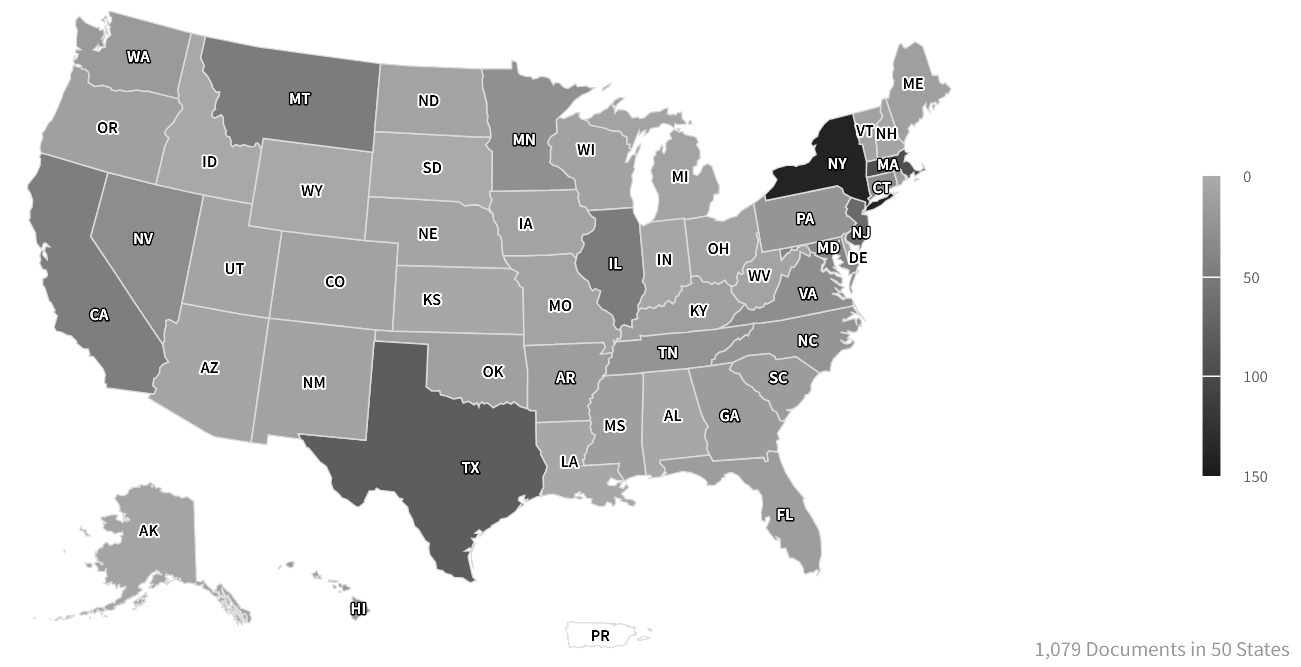

Ryan Hauser: Yeah, and a quick note on the Broadband Equity Access and Deployment (BEAD) funding you mentioned. It was a bit of a double-edged sword. The relevant BEAD funding was big enough to upset smaller states, but not quite big enough to offer substantial leverage over bigger states like New York and California. And those are exactly the states where a lot of frontier lab activity is taking place.

Matt Mittelsteadt: Yeah, and to be clear, there were a couple of versions of this. There was one version of the Senate bill that appeared to attach it to a much bigger pot — something like $42 billion in potential funds. But the ultimate version connected this to a pot of $500 million. As you mentioned, in my opinion, with states like Wyoming and Montana, whatever slice they might have gotten from that pot would’ve potentially been a pretty good incentive to accept this, especially since a moratorium is something they might be tilting towards anyway.

But for states like California, which has a budget of about $321 billion annually, some sort of slice of $500 million — call it $50 million if divided equally — probably wouldn’t have been enough to compel them. Who knows? But if you break that down by population, that works out to a dollar and change per resident in California. There are similar figures in states like Texas and New York. I’m not sure if we would’ve ended up with a complete universal moratorium. I think this would’ve been accepted by only some states and rejected potentially by states like California.

Ryan Hauser: Lauren, how did the moratorium fit into your daily operations? What’s your postmortem?

Lauren Wagner: Yeah, as I mentioned, my hobby is defeating bad AI bills. I was intimately involved with policy advocacy around SB 1047 last summer, which was the big AI bill out of California. I wrote about that. I spoke about that. I organized industry coalitions in the background to push forward different ideas about the bill, and then ultimately, Newsom ended up vetoing it based on some of those activities.

There are new state-level bills that have popped up that I have taken issue with. When this was included in the One Big Beautiful Bill, I thought, “Oh, great, maybe I won’t have to do this. I won’t have to provide more analysis, or maybe we’ll just be able to look past these bills that have been proposed.”

When it did come out, I was surprised by the 10-year timeline. I thought that was quite a long time, given how fast AI is moving. When I spoke to folks who had been involved in developing the language around the moratorium and how it’s included and being tied to budget, the first things that stood out to me were the 10-year timeline and tying it to budget allocation. In speaking to folks who had been intimately involved in the process, I heard from them that, “Oh, 10 years was just a starting point. We imagined it would be negotiated down.” And then when talking about tying it to the budget, it was like, “Oh, we actually crafted it in a way so that this will get through and the parliamentarian won’t take issue with it.”

So, what you see is not actually what you’re going to get. Maybe the general consensus or people’s first inclination when viewing the moratorium was not correct. When you’re looking at these tight timelines — Trump gave a certain date for this to have to be pushed forward or not — it’s more like, okay, how are we going to get there? Are we going to be able to educate people who have stakes in this? Will we have the ability to push it forward or not based on what’s actually happening here?

Like Matt was saying, it changed so many times, and people are trying to do real-time analysis. So, those were the first instances. Then you had Congresswoman Marjorie Taylor Greene, Vice President JD Vance, and other people providing public commentary. With some of the points they were making, I thought, you know what, that’s right. If you’re evaluating the issue from a specific perspective, yeah, this is an infringement on states’ rights. They’re not going to be able to innovate on policy during this period, whether it’s 10 years or negotiated down to five years.

I like ”AI as normal technology” — but in some instances, in this policy arena where states like California and New York are stepping out and potentially regulating in a way that will be precedent-setting both for the country and internationally — it is different. There are ways to rebut some of the pushback, some of the issues that people took with the AI moratorium. But that would’ve required real tag-teaming, coalition building, and a repository of reliable information. It’s coming from think tanks, it’s coming from people with different political perspectives and industry. It’s just really hard to do all of that and get it together in such a short period.

Ryan Hauser: Your hobby remains intact, and you can keep defeating bad AI bills.

Lauren Wagner: Thank you… Thank you so much.

Grand Old Party

Ryan Hauser: Were you surprised by the remarks Vice President Vance made in the run-up to the votes? On the comedian Theo Von’s podcast, he really seemed to waffle. Did the administration have a coherent plan for this legislation?

Lauren Wagner: It’s always hard to decode people’s motivations. They were speaking specifically about Blackburn in Tennessee and the Elvis Act. Eventually, she did negotiate with Cruz, and they ended up having these carve-outs and negotiating from 10 to five years. Ultimately, that wasn’t enough for it to get through for a variety of reasons, but it could have been that JD Vance was trying to play into that and show support so that she would be able to move on certain things and so they could get to a point of negotiation and alignment.

Or it could be that they really didn’t have alignment internally within the party. I was surprised when JD Vance was on the podcast and didn’t really come out strongly with a clear rationale for why this is needed — he didn’t substantiate it or go into it — especially because Theo Von has such a large audience. Instead, it was, “Yeah, I can see both sides. I don’t know if it’s the best idea.” That was an early indicator. I don’t know how this is going to go if we don’t have, on podcasts and externally, really strong leadership and a clear narrative around why this is needed.

Ryan Hauser: The administration started off strong in February. You had a speech by JD Vance in Paris saying, “Hey, this is going to be the American approach to artificial intelligence.” I’m not sure how the moratorium failure fits into that. The point here isn’t to criticize the rollout of the strategy, but it does make me wonder what we can expect in the future.

Matt Mittelsteadt: Vance is waffling on this. This is an issue, frankly, that I waffled on myself. It was very complex, and the timelines to fully comprehend it were very short. What’s interesting about Vance’s waffling is maybe a reflection of the Republican Party writ large. I mean that in terms of where they are in their almost complete but ongoing transition from a much more pure free-market position towards something else — a MAGA-type coalition that might have more skepticism of Big Tech and things like artificial intelligence. In his comments, that was just laid bare, right? There are these two versions of what Republicans could be that are at odds. This issue brought that to the fore in many ways.

Ryan Hauser: Fusionism 1.0 was a coalition between free-market advocates, traditional conservatives, and anti-communists. Now, perhaps, we have Fusionism 2.0, which ties together social conservatives, economic nationalists, and Silicon Valley technologists. If the first coalition seemed tenuous, the second one… We’ll see how long it holds. Lauren, do you think tech companies were ready for this, or were they more or less caught off guard? What was the attitude like on the ground?

Lauren Wagner: From what I’ve heard speaking with other folks, specifically within policy think tanks, they felt that industry came in quite late to this. The idea that this was a Big Tech push to go carte blanche — do whatever you want and not have regulation - that is not really proven by the facts on the ground. Big tech came in quite late in terms of expressing their thoughts on this.

I read a lot on this. I listened, and it didn’t seem to me like the loudest voices in the room were from the Big Tech companies saying, “We need this.” It was a cacophony of a lot of different voices. Take the “Little Tech Agenda” - if we want to pull the Y Combinator, a16z words from last year that really were pushed around SB 1047. That says you need to create a policy environment where startups and founders can actually build, and there aren’t overly burdensome compliance and regulatory costs.

That approach extended through this conversation about the AI moratorium, so there was a lot of confusion on the ground. I speak with folks on all different sides of the political spectrum, whether philanthropists or people representing employers who thought that this was a great idea. But when you actually speak to them, they’re like, “Oh, yeah. I didn't really think of that.”

So, it seemed like people had a gut reaction to the moratorium. They didn’t really have much time to think through the second-order effects — or, if we don’t have it, then what happens? It was just this idea that “Big Tech is winning.” It was a sense that we’re going to be in this environment where there’s absolutely no regulation, and companies can do whatever they want, and that’s going to be terrible for the average person, just as it’s been terrible having social platforms not be regulated, and look what happened there.

It was this idea that history is repeating itself. We didn’t get regulation done during the last platform shift. We need to start thinking about that early and get it done quickly. Now with the AI revolution, a lot of those sentiments hold for this moratorium.

Little Tech, Moderate Trouble

Ryan Hauser: I am wondering how you’re looking at the current macro environment when it comes to AI firms, big and small. Do you see the failure of the moratorium as being essentially a gift to larger firms? They can better stomach the cost of regulation. So, maybe this is going to help them get ahead, help them stave off disruptors who might pressure the incumbents?

Matt Mittelsteadt: It’s a little uncertain. It depends on what happens with state AI regulation. Of course, we are seeing bills come close to passage in states like New York and Texas. California is taking a few more volleys at this. In terms of smaller actors collectively, we could very much start seeing a patchwork problem where we have a collection of state laws or even 50 state laws that make it very difficult for smaller insurgent players to challenge larger tech firms like Google or Meta.

OpenAI is not quite “Big Tech,” but it’s getting there. It’s certainly the incumbent leader. We could see a playing field where it’s just much more costly for them. That said, I do think that it’s maybe a bridge too far to suggest that Big Tech wants this. I personally haven't seen direct evidence, and it could be that they want to do some sort of regulatory capture scheme. But overall, I still think the biggest firms have been in opposition to these types of things. They're not actively trying to create some sort of giant scheme that will embed them as the leader of the landscape by making it too costly for anyone to compete with them. That certainly could be a result, but I’m not seeing the intention.

Lauren Wagner: Yeah, I don’t think there’s necessarily a coordinated nefarious plot by the big companies to do this, but certainly big companies can staff up teams quickly and pay the right salaries to get the right people in the room so that they could bear this regulatory burden and all of the compliance costs that come along with it. I do view it as something that’s not great for little tech. So yeah, we’ll see what happens.

Ryan Hauser: I recently saw a TikTok job ad on LinkedIn in the United States for a state-level advocacy position with a salary range of $200K to $500K. Are we going to see more firms basically taking that strategy? Some were putting a lot of resources into Washington to move the needle. Now the action seems like it’s going to be in California or in Texas.

Lauren Wagner: When I was working on SB 1047, we did see even some larger companies caught off guard by the speed of activity within the state of California. A lot of their efforts have been focused on the federal level, so I think we will see more investment in state-level initiatives from these big companies.

I’ve dedicated myself to mainstreaming safe and trustworthy AI. A lot of state-level legislation I've seen doesn’t help us achieve that goal — safer technology for the people. Now it’s about actually interrogating legislation bill by bill. I’m seeing if the way they’re set up — the new mechanisms that are introduced — if they actually achieve their ultimate goal. A lot of the legislators have said AI is unsafe.

Matt Mittelsteadt: People often overestimate the bandwidth that any given firm or organization has. Even tech companies as prominent as Reddit or OpenAI — many household names — actually have very small policy arms. They don’t have big teams. You can count them on your fingers. These companies can’t necessarily comment on every single bill, or get their input into the bill, into the legislative process, and help refine things into something that might improve trust or minimize harm.

Very few firms have the ability to do a total 50-state strategy on top of the federal government and on top of every other country on earth. Just a handful of firms — Meta, Google, and a few others. With everyone else, you have to assume small teams. Think tanks and advocacy organizations often just have one or two people working on these issues.

The assumption that we can get enough input and get these things to a good place when it’s all happening all at once is not the best assumption. There’s just so much going on, too much for any one person to handle. Even the moratorium caught everybody off guard. It’s a worrisome state of affairs for good policy-making when there are just so many different variables changing all at once.

Ninety-Nine “No” Ballots

Ryan Hauser: How do you view that final 99-to-1 vote? My own impression is that it was more of a signal, like “Hey, look, we’re just not getting any movement on this — let’s move on.” It wasn’t a robust indicator of sweeping opposition or a strong set of revealed preferences.

Matt Mittelsteadt: Yeah, I think that’s exactly right. The most specific signal is that Ted Cruz voted against his own bill here. I think that if this were truly the count of opposition, Cruz wouldn’t have been on board. There were plenty of other senators who were at least sympathetic or even voiced support for it who also voted no. They just got everybody to vote no so that you couldn’t really tell who was in favor, who was opposed. That way, in the future, when they do maybe another version of this or something else, they don’t have to mess around with past votes.

Lauren Wagner: I thought it was interesting to see the chatter on X. You had a lot of folks who work for AI safety organizations, and they were like, “I thought we weren’t making any progress, and then we won, and this is amazing.” It’s just interesting to gauge the chatter in terms of the other spheres of influence that sit outside of the government.

Ryan Hauser: Was the political opposition from some GOP senators and governors a tipping point that will lock in future federal AI efforts? Arkansas Governor Sarah Huckabee Sanders led a group of 17 GOP governors opposing the moratorium. Has the coalition in favor of AI innovation been weakened as a result of this?

Lauren Wagner: To me, it’s just not necessarily a narrative breakdown, but so many narrative gaps that need to be filled. I’m trying to figure out how we do that effectively and work together. The idea that the moratorium was taking away states’ rights and concentrating power within the federal government — I totally agree with that.

But at the same time, the AI legislation that’s being proposed in states like California and New York would be precedent-setting, both in the US and internationally. These proposed laws are not just doing small regulations that other states can adopt so it’s a net positive all around. In some cases, you are really imbuing state legislators with the same power that you’re so fearful of giving to the federal government.

There’s a lot of work to be done to create an alternative, more factual narrative around all of this. We have to identify the two or three key threads needed for interrogating and thinking through good and bad state-level AI legislation.

Ryan Hauser: Around mid-July 2025, Kalshi showed a 25% chance of federal AI legislation passing before 2026, which seems high to me. The Metaculus community forecast had it at 8%, which seems more reasonable. What are your thoughts on the likelihood of comprehensive legislation being passed before the next Congress?

Matt Mittelsteadt: It would depend on how we define comprehensive legislation. It is worth noting that we actually have passed AI legislation this year. There was the Take It Down Act, which was a deepfake regulatory bill. There are things happening. They’re not necessarily comprehensive, but they are happening.

In terms of something bigger or really hard-edged regulation, I would put that at a decently low probability without knowing what that regulation might be. I wouldn’t expect some sort of EU AI Act, an all-encompassing ruleset for AI. But I could expect certain issue-specific regulations to be passed — maybe facial recognition is an area in which people think that, because it could be used to violate civil liberties, maybe we need some stricter rules on how it can be deployed across the country. Maybe on issue-specific areas like that, we could see some progress where coalitions can be much more easily built and opposition might not be as fierce.

I also wouldn’t put it past Congress to look into investment-based approaches, investing in certain safety technologies, perhaps through NIST or DARPA-like moonshot projects. They are doing some of that already. Perhaps there’s a grander version we could pursue. If some big event happens — some sort of cyber attack or what have you — that could very much change the narrative.

Lauren Wagner: I agree with all of those things. I would really like to see issue-specific legislation gain more traction and also more work on standards and grant-making that really activate public-private partnerships within the broader ecosystem. That would really empower folks doing good work.