Toward Perpetual Violence

Progress cannot exorcise our demons

The killer is typically young, male, and detached. He wants to impress, possess, or kill his competitors, companions, or self. He has, for a moment, an overwhelming sense of agency and empowerment, even liberation. He thinks of himself as an arbiter, humbling the proud and raising the meek. His cause feels righteous and primal. When finished, he considers himself cleansed by a sacrificial purity — a neural flood better than any high from any substance or simulation or sexual liaison. Then comes despair, the same thick morass he tried to escape, only now darker and deeper. The contagion spreads, and the cycle keeps on spinning.

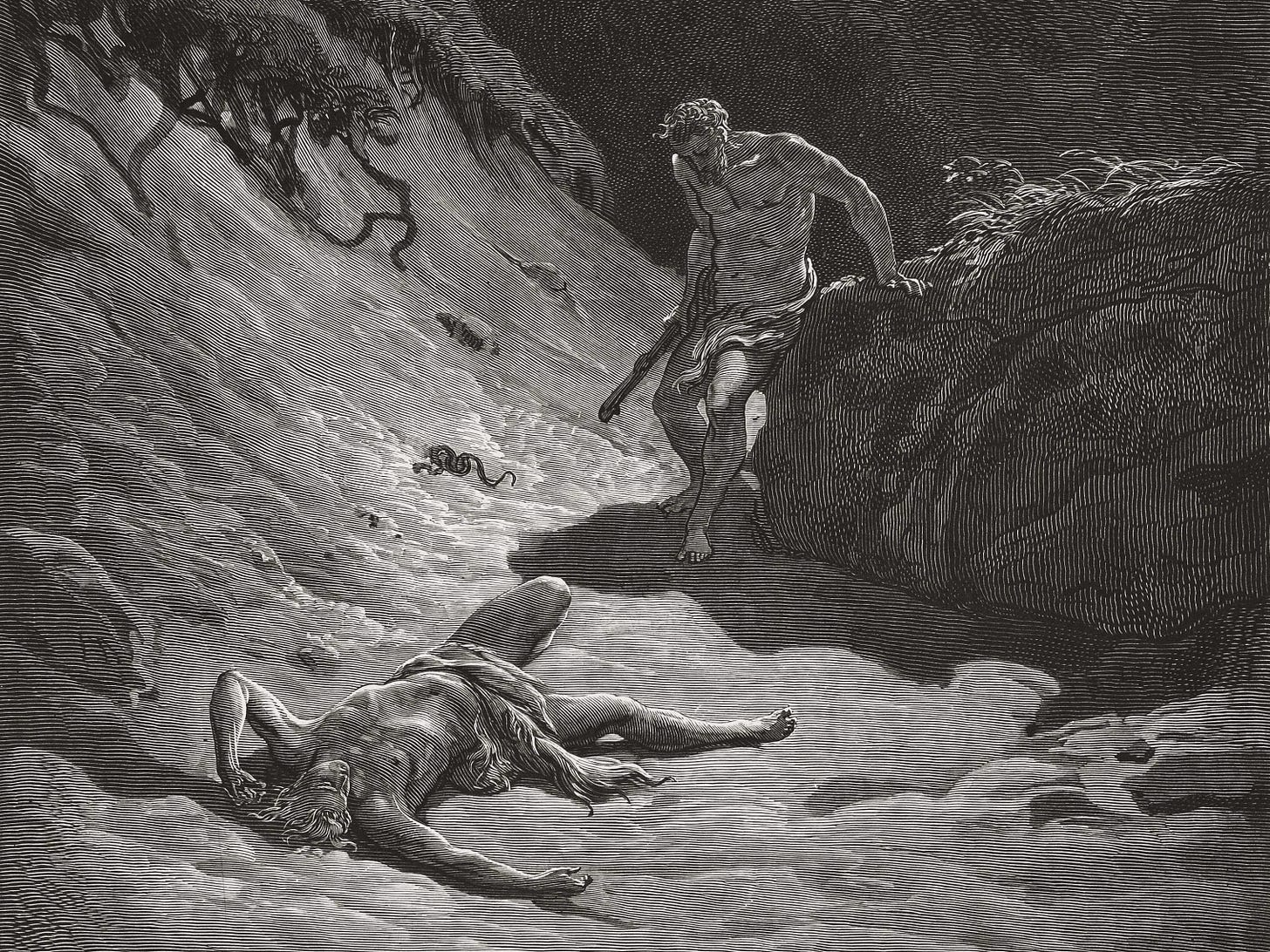

These are the “demonic males” of our species — from Cain and Achilles to Ahab and Kurtz. They’re on every screen after every recorded act of violence. To understand them is to understand ourselves. Observant readers will know I am borrowing that vivid term from prior work on the evolutionary origins of violence. This literature has merit, but it is incomplete. The patterns of human violence skew overwhelmingly male — both as victim and offender, as well as individually and collectively. That is uncontestable. My argument, a sketch of sorts, goes further and should not be limited to any demographic boundary, however enticing.

Violence is an ineradicable part of human nature. No amount of material progress is likely to remove it, though it may temper it.

The roots of violence run deep in our genes and culture, and we only need the right conditions and enough time to let their poisonous fruit grow — first in our own souls, then in the body politic. In that sense, all violence is deeply political, if not always partisan. The word “political” is certainly a strange qualifier when appended to violence. It’s like referring to “biological” or “psychological” violence, as if violence among homo sapiens were not always those things, as if every act of violence could be classified apart from what Saint Augustine called the libido dominandi — the “lust for domination.”

You can look to evolutionary anthropology on these points, but I don’t mean to suggest that collective blameworthiness should supersede that of the individual. Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn emphasizes this in his reflections from The Gulag Archipelago:

Gradually it was disclosed to me that the line separating good and evil passes not through states, nor between classes, nor between political parties either — but right through every human heart — and through all human hearts. This line shifts. Inside us, it oscillates with the years. And even within hearts overwhelmed by evil, one small bridgehead of good is retained. And even in the best of all hearts, there remains… an unuprooted small corner of evil.

While most physical violence is perpetrated by men in groups — a stylized fact policymakers must take into account — the appetite for violence sits in each of us as individual persons. It makes no distinction between ethnicity, class, sex, religion, ideology, or party even as it runs through those things.

Were it possible, eradicating our bent toward violence would likely require totalitarian eugenics. I mean the kind of mass social engineering that has already failed catastrophically across 20th-century utopian movements. But say we have advanced scientifically and morally beyond those projects. Maybe we can find the right genes, turn them off, or modify them? Maybe we can merge with our machines and delete our violent elements? A state could prompt this transition voluntarily at first, nudging compliance. But there are always holdouts. Force is needed to complete the effort, to reduce the risk of violence to absolute zero. The usual pitfalls of central planning and mass coordination also come into play — the same obstacles the PRC faced when pursuing its one-child policy. But even if a state overcame these challenges and forged a new order, the last men standing would still form a vast, violent apparatus. Would they wither away? Would they toggle off their domination? This is all deeply speculative, but these scenarios are suggestive. Imposing your will on a weaker agent unable to retaliate often yields sizable gains for the dominant agent. Why stop when you get on top?

Cooperative approaches to eradicating violence are inadequate too. They are typically slow and unlikely to reduce the risk to absolute zero. The greater the success of voluntary reform efforts, the greater the reward for using violence to form coalitions and impose one’s will on those who remain peaceful and compliant. While I accept the doux commerce narrative — the argument that cooperative exchange tames our passions and sublimates our interests — this state of affairs has historically only come about by using force to secure the interested and restrain the passionate. When non-violent resistance works, it is generally accompanied by some backstop of threatened violence. MLK and other civil rights leaders were successful because they persuaded the nation’s voters and officials to intervene with force or the threat of violence to bring about the badly needed reforms. Federalism, to be sure, made this tricky. But the executive branch was ready to intervene — and did so — when needed.

Put another way, both violent and non-violent strategies for eradicating human violence are likely to fail.

The best we can hope for is not the eradication of violence, but curbing our appetite for violence through self-governance, both individually and collectively. By that I mean bringing man into community and commercial society — making him a little less inwardly bent, less focused on domination and more focused on recursive self-improvement in pursuit of a far greater good. That must happen at the personal level, but it can be enlivened or stymied by our moral-ecological circumstances. Fortunately, we have a good model for fostering reasonably peaceful productivity. The historical reduction of violence seems to come about by way of three overlapping pathways: 1) liberal social norms, 2) state capacity, and 3) the technological and economic growth that emerges in this context.

Ultimately, however, self-governance is deeply personal. “The just man… sets in order his own inner life, and is his own master and his own law, and at peace with himself,” argues Socrates in The Republic. Plato is not arguing for a kind of emotivistic relativism that places the individual’s will and understanding above all else. He is making a point echoed by philosophers through the centuries. Order in the soul begets order in the polis. The same goes for disorder in the soul.

Note that I am making a largely normative argument for self-governance paired with anthropological inputs. I am not embracing a strong Pinkerian view that violence has declined both within and between societies. On the contrary, I am persuaded by the late Bear Braumoeller and his masterful work, Only the Dead: The Persistence of War in the Modern Age. In this research, Braumoeller statistically dismantles the geopolitical conclusions of Better Angels, leaving us with a sober respect and expectation for ongoing collective or mass violence.

Related to the persistence of warfare is the core problem that techno-economic growth increases social welfare but also lowers the cost of carrying out violence. This is a point occasionally made by Tyler Cowen, so I will call it “Cowen’s Paradox,” because I think that sounds pretty good. Others have made the same or similar points. The paradox is a core premise in Nick Bostrom’s “vulnerable world hypothesis.” A related concept is the “democratization of violence” — a process whereby “the tools of warfare are no longer the exclusive domain of nation-states but are accessible to smaller groups and individuals.” Power and plenty walk in the same direction, for good or ill.

For our purposes, we can think of techno-economic growth as the process by which more people increasingly get more options, more capabilities, and more wealth more of the time. We should expect this evolving basket of goods and services to include tools intended or modified for violence. This would not change even if we could purchase, destroy, or ban the creation or possession of every last weapon or near-weapon.

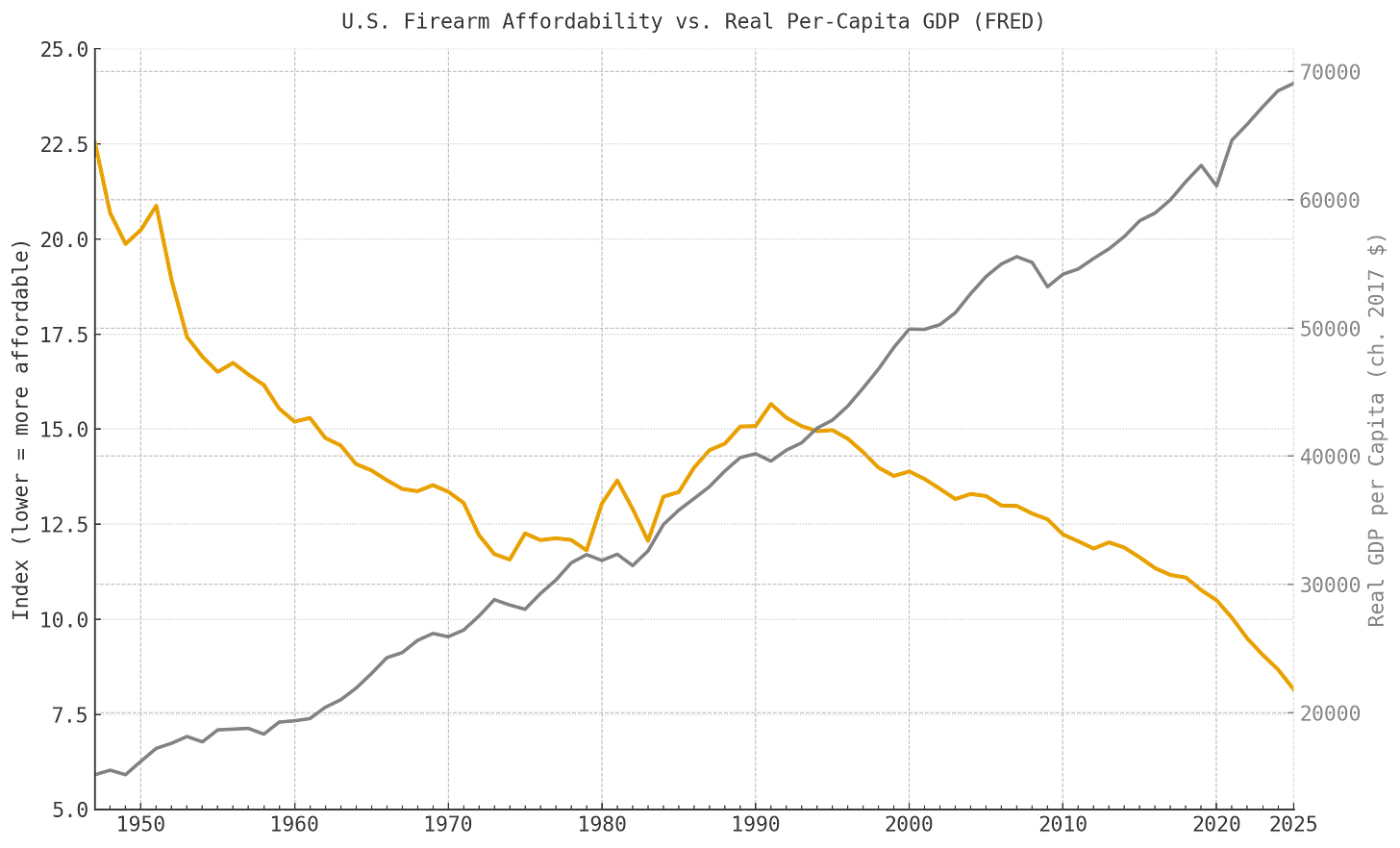

You can see the relationship between techno-economic growth and the possibilities of violence quite clearly in one limited test case — the affordability of firearms in the United States. (See chart above, “A Most Violent Proxy.”) Over the past three-quarters of a century, guns have become substantially less expensive in the US. I measured this by using FRED data to plot the average hourly earnings needed to purchase a firearm in the US (PPI for firearms / AHE), then juxtaposed it with real per-capita GDP. The chart does not show causality and is merely descriptive. Firearms have become more affordable alongside booming post-war techno-economic growth. In the pursuit of peace and plenty, we became more comfortable and better armed.

At a basic level, all technology is “dual-use” because the human toolmaker is divided between good and evil — not in equal parts, but by inclination and desire. This is a fundamental tension that cannot be resolved by banning any given technology. Now, that is not to say that each tool is equally suitable for violence or equally damaging when used. There are good reasons for restrictions on all manner of state and non-state weapons. Keeping the most destructive tools out of the hands of the most violent agents is a reasonable goal prima facie.

I do not want to focus exclusively on firearms, let alone their strange, troubled regulatory history in the US. My point is broader and gets at the rational animal who creates and deploys the tool. The trend of rising gun affordability illustrates a central point about human nature and the moral plasticity of technology — our tools are shaped by our intent, and in their use and creation, they shape us.

Humans are deeply creative, and we are particularly adept at converting anything into a weapon. We began with rocks, plants, and bones and worked our way up to silicon, anthrax, and drones. The two worst acts of non-state political violence in the US were accomplished by way of architecture, airliners, and fertilizer. Cultural learning, imitation, and innovation are the “secret of our success” — in peace and war.

Perversely, as techno-economic growth improves our material conditions, violence carries an increasingly dramatic asymmetry. The greater the peace, the bigger the jolt. Negative contagion spreads, from bad vibes to mimetic murder. Social trust is violated, within and between citizen and state. We find a scapegoat, someone to blame for the peril in our plenty. Ritual purifications are then conducted or hijacked or praised by coalitions of rivalrous “demonic males” looking to punish and restrain their opponents. The edifices used for these ceremonies are not easily swept away. They accumulate — a “ratchet effect” clicking and locking and rotating only in forward movement, outliving memories of whatever violent event demanded it.

And truly, each sacrificial offering, each incantation directed at our partisan enemy — that brazen, secret schemer — is actually rather convincing. Because the line dividing good and evil cuts through each one of us. We never have to look far to find evidence that our enemies are deeply wicked. They are evil because we are evil. We cannot speak of their capacity for good because we do not know how to speak of our own — not without great difficulty.

We can start again by looking at our inner line.