Model Convo: Ryan Hauser

On Cliometrics, Peter Weir, and Roko's Basilisk

Welcome back to the “Model Convo” series — micro interviews with researchers in AI policy and related fields. If you know someone I should interview for this series, please email me.

Background: For this week’s convo, I’ve decided to run the risk of submitting my own responses. This is a one-off, so expect more guest Model Convos in the new year!

If you don’t know already, I am a Research Fellow at the Mercatus Center at George Mason University where my job is mostly writing and editing this Substack on AI governance and emergent order.

I am also a graduate student in the Department of Science, Technology, and Society at Virginia Tech.

How did you get into emerging tech?

After leaving college in 2014, I spent roughly a decade doing various research and editorial jobs in and around Washington, DC. I knew I wanted to go deeper with one subject, but I hadn’t found the right beat beyond general economic and security policy.

I started working in tech policy in earnest in 2022 when I began a short-lived Substack called Chainmail, which looked at the geopolitics of digital finance. (You can find some of that early work here and here.) The following year, I began working as an editor at ChinaTalk and pursuing graduate studies in the history and philosophy of science and tech.

I then gravitated more and more to AI governance. I found it much more interesting — a natural outgrowth of the questions I had been asking over many years about science, tech, and philosophy. AI governance bridged questions about hardware and metaphysics in a way that was much more salient than other fields. To quote Rebecca Lowe, “The age of AI is the age of philosophy.”

Despite growing up as the son of a software engineer, I was not a native techie. I felt I was somehow disqualified from working in tech policy because of my lack of talent in econometrics, engineering, or area studies. Or because I didn’t own a smartphone before 2018 — and only after my flip phone bit the dust, no longer held together by electrical tape and dwindling hope.

As a government major at a Great Books-ish small Christian liberal arts college, I read a range of thinkers on the political dimensions of science and technology — Francis Bacon, Karl Marx, Martin Heidegger, Michael Oakeshott, C. S. Lewis, Robert Nisbet, and George Grant, among others. My fellow students and I were skeptical of “progress” across the board.

But taking Econ 101 with a professor trained at George Mason University encouraged the green shoots of mainline economics that had been growing in my brain since high school, the period where I first read Wilhelm Röpke, Milton Friedman, and Paul Heyne. Though I’m not quite sure when, I also started reading Marginal Revolution in college and eventually took an internship at Mercatus, working under Garrett Brown — now a colleague who writes at Humane Pursuits.

Near the end of college, I began to cultivate parallel interests in the history and philosophy of science and economic history — particularly the post-war, cliometric variety. These fields provided a stark contrast with the empirically light discussions that often characterized many of the most prominent writers on science and technology.

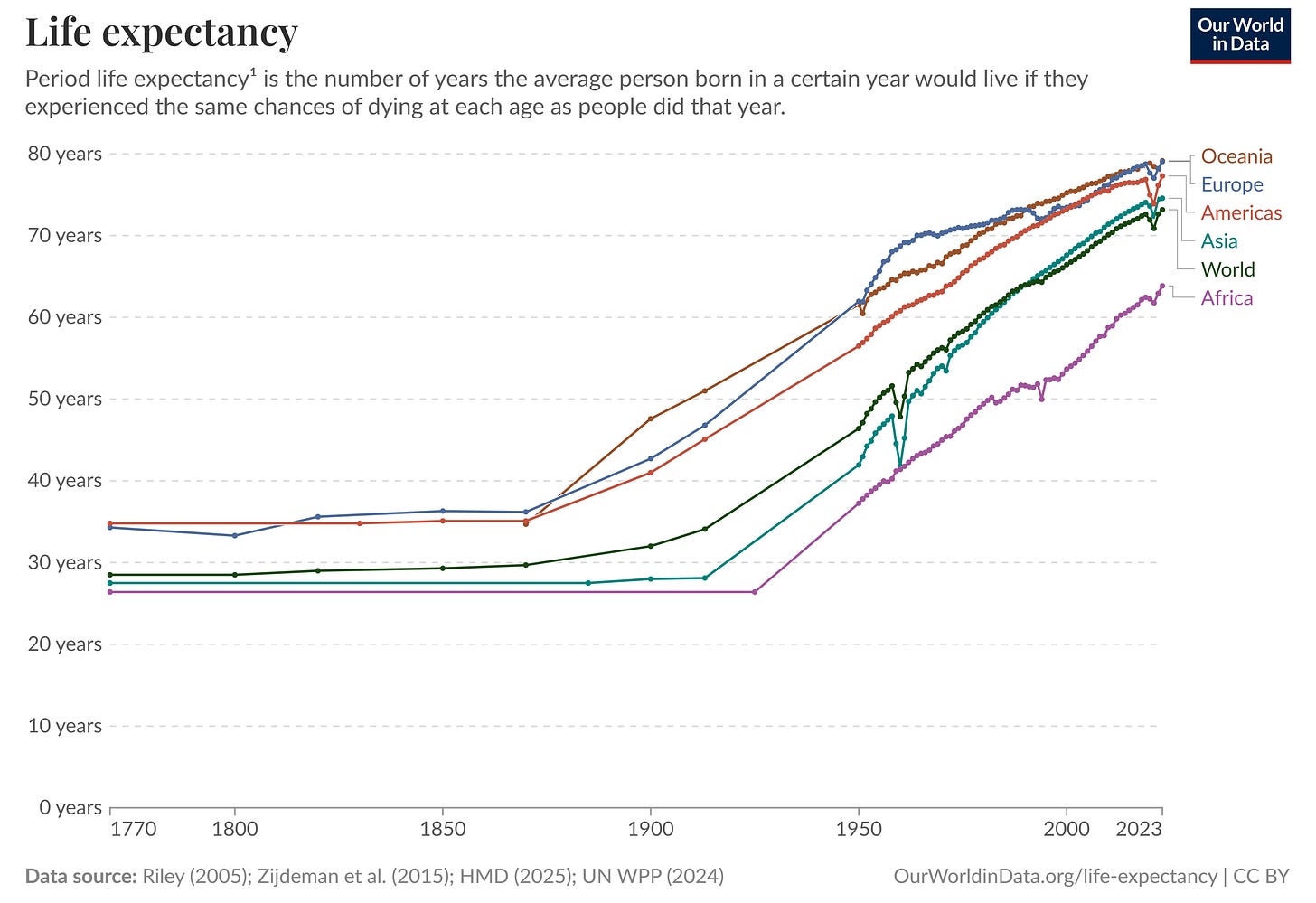

Gradually, with these new empirical reference points, the claims of the more pessimistic writers seemed incomplete at best or misleading at worst. How exactly would Neil Postman — or for that matter E. F. Schumacher, Wendell Berry, or Paul Kingsnorth — have responded to the global doubling of life expectancy had they seen it? How would they explain the misery of techno-economic growth alongside major improvements in literacy, child mortality, and maternal mortality? These authors seemed totally unwilling or unable to contend with the eucatastrophe of growth.

The critics of techno-economic growth were stuck. Writing in the shadow of the atom bomb is sobering but also comes with epistemic risks. Indeed, we should be wary of all utopian schemes. But a persistent negativity bias can nudge us to adopt or advocate for policies that restrict useful innovation. It’s one thing to live alone as a Swansonian curmudgeon — it’s another thing to impose unwarranted costs on your neighbors, to halt or slow advances in science, medicine, and national security for what is often merely an aesthetic impulse.

That said, I am still in my bones fairly pessimistic about human nature. War, especially, continues to be the major risk that could slow or halt our material improvement, just as World War I brought an end to the first era of globalization. There is no guarantee that these advancements in human life will last if we do not work to renew them and their moral-ecological roots. We’re all muddling through here.

What work of art has most shaped your views on emerging tech?

It seems impossible to pin down one discrete art piece in the weird network of experiences that shape my beliefs about tech. So I’ll just answer by gesturing toward the films of Peter Weir.

I first watched The Truman Show when I was quite young — maybe nine? That was before social media had become a core part of our daily lives. It’s the only man-disillusioned-with-modernity ‘90s flick I like — maybe the only one that still holds up.

I think the film has more in common with Dante’s Divine Comedy than with The Age of Surveillance Capitalism. The film asks, How can we know what is good, true, and beautiful when we are just so comfortably numb? In Truman’s case, his quest begins and ends with a beatific vision.

Weir’s other films also directly and indirectly take up questions about technology, which are ultimately questions about human ends and means.

Gallipoli is about the bonds of friendship being subjected to mechanized war — “the social history of the machine gun.”

Witness is about norms and belonging between two worlds — one pacifist and weirdly frozen in time and another modern and groaning in violence.

Mosquito Coast is a fairly straightforward, albeit agonizing allegory about hubris and utopia.

Master and Commander: The Far Side of the World is about a small, intense community of discovery and creativity — a “society of explorers,” to use Michael Polanyi’s phrase.

The Way Back is about escaping the planned society — about the price of freedom and man’s ability to adapt in hostile terrain.

Weir’s films often attempt to show that — even when we deny it or seek to expunge it — the world is still deeply enchanted in ways that confound and perplex us. They are films about emergent order.

What’s your most contrarian take on AI?

I am a sand-god atheist — or at least a skeptical agnostic. I tend to locate my sources of re-enchantment in other ways.

I talk about this in my “Thesis and Prospectus” launch essay:

Eschatology — theology concerning the end of days — offers an unstable framework for cultivating good governance. It makes us fragile. Claims about infinite expected value — visions of damnation and glorification — make weighing costs and benefits unworkable. Governance that is practical, decentralized, and bottom-up becomes irrelevant, even dangerous, in this vision.

So, sorry about that, Roko…

What are you reading (or watching, or listening to) now?

Nothing particularly high-brow… though I did just finish Bono’s memoir, and I think he is unironically one of the great Irish poets of our time. He’s also a solid writer and reader of literature — in conversation with the likes of William Butler Yeats, James Joyce, Seamus Heaney, and Flannery O’Connor.

Other than that, I am mostly reading about AI and the political economy of science and tech. The polywater affair is also a recent interest of mine, so I am reading about that in preparation for a long essay on the subject.

Go-to emerging tech music track?

I view all technology as being “dual-use” at a core level. The desires of men writ large are always a mixture of good and evil things. We can’t help it.

“Good Technology” by the 1980s English indie rock band Red Guitars has unmistakable Labourite vibes to it. We should look past that — the lyrics need not be taken as pure irony. They are in fact mostly singing about good things.

But life is full of tradeoffs, and There Is No Such Thing as a Free Lunch.