The Best a Man Can Get

Sex, Technology, and the End of Clean-Shaven History

The more I watch this 1989 Gillette commercial, the more it hits me at an intestinal level. On the first viewing, it is saccharine. It gets a slight eye roll, maybe a nostalgic flicker stamped out before it burns something. On the seventh viewing, I’m undone.

The reasons are straightforward. After several years of wear and tear, my own marriage has seen better days. The ad also reminds me of our earliest family camcorder videos with my own dad, on-screen as a lean Air Force vet returning to civilian life with three kids in tow and more on the way. After about a decade in uniform, he was back on the grind in Nowhere, Ohio — down the road from Neil Armstrong’s hometown — and supporting a quickly growing family on a single salary. He was able to do this thanks to the 1990s tech boom alongside the diffusion of solid technical education — courtesy of the Community College of the Air Force. The military gave him critical, on-the-job training, honing his talents by way of old, bulky computer systems tracking global furniture inventory. (Even B-52 pilots need a break.) He told me these computers were “the size of washing machines,” and I pondered the marvels of tech progress whenever I emptied my overflowing hamper in our household laundry room.

He was 25 when I showed up. (I didn’t even own a car at 25.) That was the year right after we won the Gulf War by air power alone — for the most part — and a few months after the Soviet Union collapsed. Not long before that, Dana Carvey was poking fun at George H. W. Bush, the clean-shaven chief WASP and former head spook who managed American affairs with prudence and decorum. 1992 was also the same year that marked the halfway point of Michael Jordan’s incredible fourteen-year run. The US Summer Olympics “Dream Team” was spreading the good news of America’s athletic greatness — and the world couldn’t get enough.

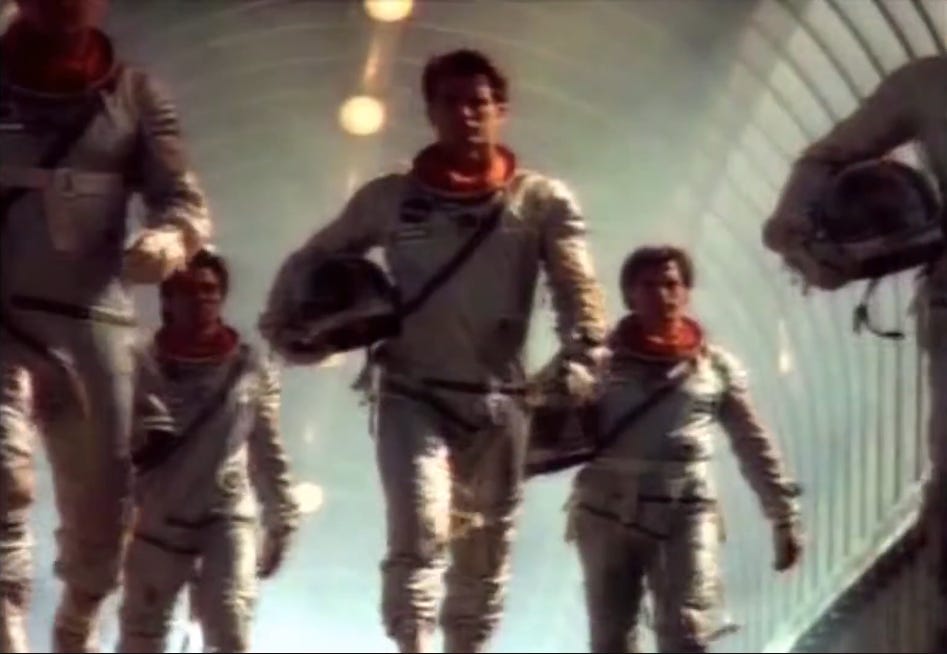

Back to the men’s hygiene commercial — in sixty seconds, we are transported through an intense, anthropological montage. It’s a celebratory psychodrama of fathers, sons, husbands, marriage, tradition, love, friendship, community, markets, discipline, excellence, camaraderie, exploration, adventure, aesthetics, joy, kindness, striving, building, growing, grinding, and becoming. There is no punchline. There are no cavemen selling car insurance, and there are no surreal antics on behalf of a struggling sandwich chain. Watching that Gillette commercial is like watching Goose and Mav settle into their fully developed prefrontal cortexes. They take good risks, and they rightly order their passions and interests in a way that you know, deep down, even the Iceman would have to respect. If it turned out the commercial was just state-sponsored propaganda for our unipolar moment, you couldn’t be mad. It would honestly make it cooler, as if Ronald Reagan and Steve Jobs forged the idea at Camp David after probably too many shots of Japanese whisky.

But all this for a razor? When the commercial aired, we were doing something different — as a family and as a country. We were winning. The hardest days were behind us. We were getting religion — or at least the evangelicals were. It was a fresh restart, again. Hope was full-spectrum. We had a new (for us at least) three-bedroom home at the edge of a small rural town. My dad’s first salaried job, after he left the Air Force at the end of the Cold War, was working as a software engineer at the Alcoa Corporation. This was the storied US aluminum mining firm that got started in the late 1880s — about the time builders of the Washington Monument topped off the obelisk with that same rare, coveted metal. Alcoa later became somewhat famous by helping the US literally build the Apollo program, eventually allowing America to win the race to the moon. But the beige office complex in semi-rural, semi-urban Ohio certainly bore no obvious marks of interstellar travel. Instead, it consisted mainly of windowless rows of fluorescent-lit, felt-walled cubicles lined with Dilbert clips, Pez dispensers, and NFL coffee mugs. “Bring your whole self to work.” I have nothing but good memories of that place. When my dad used his access card to show my siblings and me the quietly humming server room, I thought for sure he might be a spy.

Yet despite all the progress and abundance of the period, the 1990s ultimately bore some bitter fruit. The same circuitry that wired our prosperity also rewired old vices. This was something the Gillette commercial could not foresee, even with all the glistening bodies and intense acts of sublimation. The explosion of internet pornography followed broader trends in videographic and computational innovation. The diffusion of sexual technology arguably gave the internet one of its first high-demand use cases — dopamine you can download — a nuisance for many but atomization for some. Now, don’t get me wrong. The tech didn’t create this appetite, though it did engorge it. New digital networks made the market vastly more efficient. They both stimulated and satisfied consumer demand — what behavioral economists call “hedonic adaptation.” Fantasy and reality now merged for those who found the off-screen world too painful and too boring. Instead, new worlds of pixelated bliss promised the viewer all would be well — at least for a moment. Both then and now, we have yet to develop the right antibodies to deal with this.

The fundamental drivers of this dynamic have existed for as long as we’ve been mammals. Our preference for living in dreamlands certainly predated dial-up. My forebears in particular had many failed attempts at personal liberation, and they had little help from digital hardware. One, a minister, was always clean-shaven and well-dressed. Another, a machinist, was scratchy and plainclothed. Both kept their paramours across town and their Playboy under the sink. All respectable men did. Later, hidden networks could be stored on a single hard drive. We were the same creatures with the same desires. Only, now it was much easier to get the goods — “smaller, faster, lighter, denser, cheaper.”

The social and technological groundwork for this liberation, however, had been laid well before Gillette aired its Super Bowl commercial — an ad that placed dependence at its core. In the decades prior, it was the counter-cultural beard that set the standard for American men. Before high-end disposable razors reached their aesthetic peak, just as the Berlin Wall was being discarded, bearded men ruled the underworld. The ‘70s and ‘80s especially had plenty of hidden faces. The Grateful Dead, Steve Wozniak, Paul Allen, Frank Serpico, and way too many hippies and Jesus Freaks took their inspiration from John the Baptist and John the Beatle. They did this to let us know they were fighting the man, or at least not joining him. In fact, they were building a whole new system layer on top of this concept. These things come and go, but Americans love a good rebellion, and we don’t need many reasons to start one. It’s part of our source code.

Gradually, we cleaned up in the 1990s — except for whatever was going on with the Cobanians and their angry grunginess. But this era of good feelings came to a hard close one September day. Everyone who witnessed the carnage had lines seared into their faces after that — even those who watched from what was supposed to be a safe distance, from the televised glow of every break room and living room in America. Whatever we believed about peace and plenty was greatly diminished. In the twenty-year war that followed, fathers and sons fought and died in the same dry valleys, and the beard came back as a symbol of jaded masculinity. It was less about bespoke rebellion and more about unconventional grit, courtesy of SOCOM grooming standards. Even Jim from The Office looked the part when Michael Bay sent him to Benghazi. But we could never go back to 1989, and we kept our faces covered. Even the top brass joined.

And all that is fine. Personally, I dislike shaving and have since I began doing it in earnest. I’m not counting those pre-pubescent, fake-razor practice sessions common among young boys. I liked those. But in general, I tended to be bad at shaving and generally came away with more burns than it was worth. My first razor was probably something disposable from Gillette, the kind a recently minted teenager might need once or twice a week. After that, I got a hand-me-down electric razor that needed to be plugged directly into the outlet. It boasted a springy, curly cord to keep it from accidentally falling into the sink water and searing your face in a way even a Turkish barber could not endorse. I gave up shaving as a temporary long-term experiment after the failure of my first serious relationship. I grew into it and never felt the urge to change course.

I do happen, however, to use the same Gillette deodorant my dad got me started on two decades ago. “Cool Wave,” the kind of clean corporate smell that gently wakes you up in the morning and makes you feel like you should deposit more money in your 401(k) — or take up golf. (Scratch that, golf is lame. What were you thinking?) I actually use the “clinical strength” version of that Gillette product for what are hopefully self-explanatory reasons. There was a time — the aforementioned romantic-historical inflection point — when I tried to switch to an organic deodorant, the closest I ever got to being a hippie. But the experience was horrible and short-lived. To put it bluntly, my Teutonic thermo-regulatory system has greatly benefited from modern consumer R&D. I have my forebears’ genes — the voice, face, manners, interests, and obsessions, and that’s why I had to join a twelve-step group.

It’s easy to notice aluminum pit stains on a white undershirt and sharp razor burns on a smooth face. Both are unpleasant and call your attention to the fact that things are not working out quite the way you had hoped. But you want to try to make an effort to be presentable. So you split the difference, and you trim your beard. It’s less barbaric, more dignified. Maybe your wife notices. Or maybe she’s got much better things to do than to performatively greet you, grasp your face, and gaze longingly on your shorn visage after you return from your daily commute. So, you pick up the scissors on your own behalf. It takes practice, but inflation is enough to drive you to the DIY economy anyway. You do it for you. Maybe you walk a bit straighter now, if you like the result.

And you do… most of the time.