The Bot Short

Burry's bet doesn't mean a long-run AI bust

Scion Asset Management is making big bets against AI. Or at least, that’s what the headlines say. The hedge fund led by legendary investor Dr. Michael Burry has bearish puts on one million shares of Nvidia and five million shares of Palantir. Whether Burry is right or wrong about these companies, he’s doing what hedge funds do best — providing market discipline and absorbing risk. But don’t make the mistake of thinking today’s leading tech firms are the new Pets.com or subprime mortgage crisis. AI is here to stay.

The 13F SEC document that revealed Burry’s investments right now only shows quarter-end long positions, not option strikes, premiums, or expiries, and neither shorts nor hedges. So, we should keep our inferences modest. But there are other clues floating in the ether.

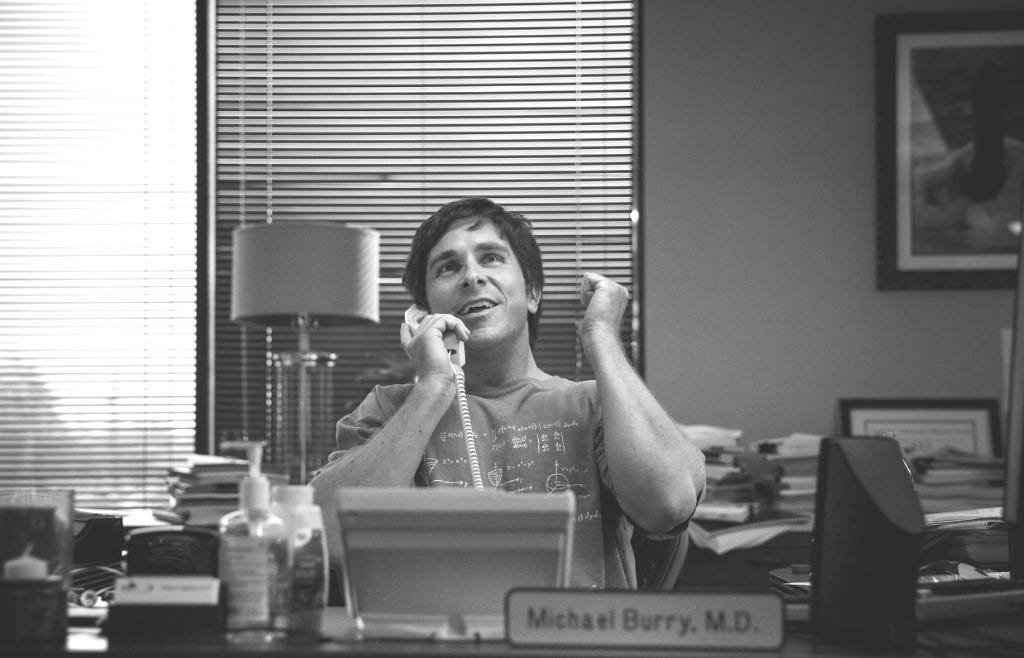

When you look at Burry’s profile on X — writing under the alias “Cassandra Unchained” — you see that (as of publication) only five posts remain despite the account’s birthdate of November 2011. The others have been deleted, perhaps prior warnings of manias, panics, and crashes. Two of Burry’s posts — they used to call them “tweets” back in 2008 — feature the visage of Christian Bale, the actor who played Burry in what is unfortunately one of the most successful financial movies of all time. (More on that later.)

Who can blame Dr. Burry for taking pride in his cinematic doppelganger? Bale’s character in The Big Short is iconic, clad in shorts and a T-shirt, an intense, autistic drummer and analytic savant with an unused MD, fake eye, and the raw cognition to move mountains of data. Forget Michael Douglas’s Gordon Gekko, with his weirdly fancy suspenders and pleated pinstripe pants. The cinematic Burry was made to bring low the Gekkos of this world — ratio contra imperium. It’s a strategy that tells the rest of the world to get lost, to put it politely. It’s what this country was built on, “FU money,” to put it much less politely.

One tweet shows a picture of Bale looking at a screen, perplexed. Burry’s caption reads: “Sometimes, we see bubbles. Sometimes, there is something to do about it. Sometimes, the only winning move is not to play” — an apparent homage to WarGames. Beneath, the replies are filled with derisive laughter and the absence of forgetting. One netizen opines that, “You’ve called nine of the last one bubbles.” Oofda. But we needn’t be so glib. After all, this time may be different.

Two other tweets Burry has posted offer a teaser trailer for the thesis behind his recent positions against Nvidia and Palantir. It is a story in five images:

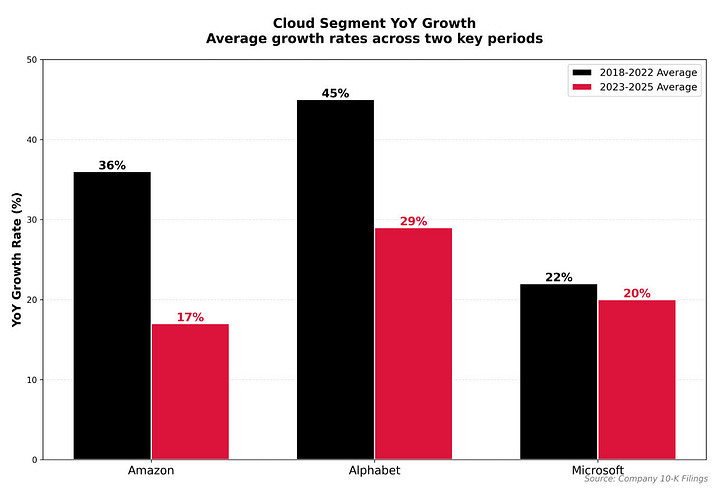

#1 shows a decline in average year-over-year growth rates for cloud services from the period of 2018-2022 to the period of 2023-2025. There are double-digit drops for Amazon and Alphabet and a single-digit drop for Microsoft.

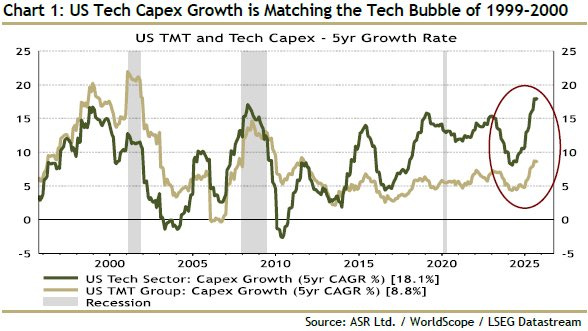

#2 charts the five-year compound annual growth rate for US tech capital expenditures.

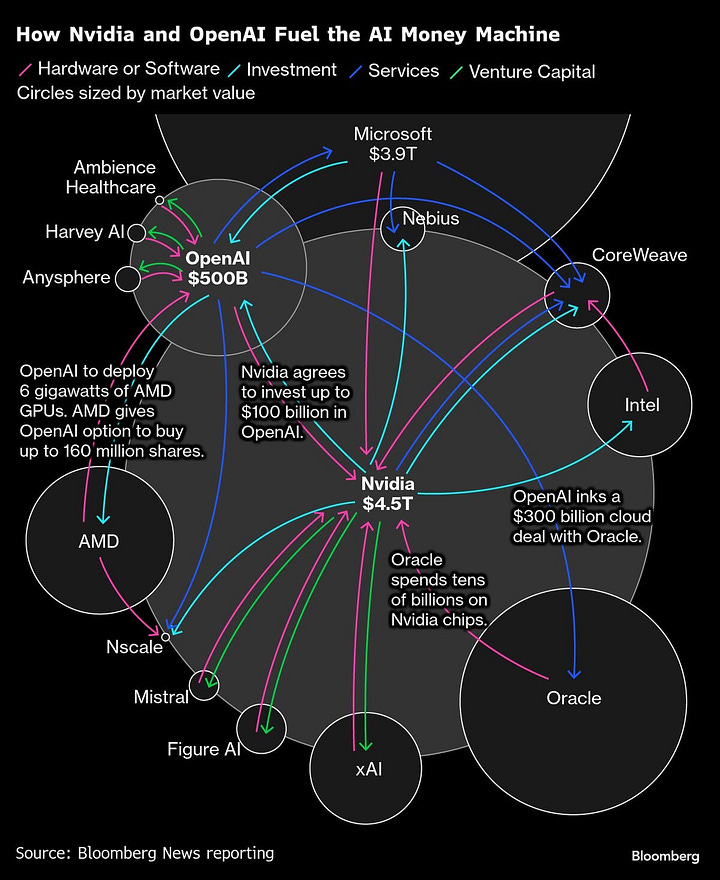

#3 is a diagram mapping recent investments in the AI space. It has become memetically commonplace in online discourse and purports to show the incestuous financing of the AI boom. (See Noah Smith on this matter.)

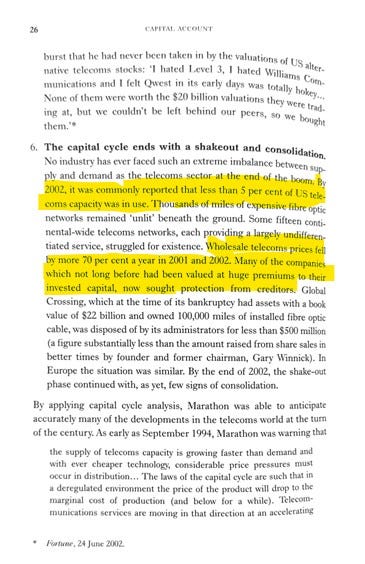

#4 is a page from the investor and historian Edward Chancellor’s Capital Account: A Money Manager’s Reports from a Turbulent Decade (1993-2002), detailing the aftermath of the Dotcom Bubble of the early 2000s.

Aaron Slodov — an AI and manufacturing entrepreneur and reindustrialization advocate - replied to Burry, ”Did you guys think summoning the machine god would be cheap?” It’s a good question. But this is America, so we really were expecting a Blue Light Special on the new sand deity, if we’re being candid.

Meanwhile, OpenAI is reportedly looking to raise $7 trillion in capital for a new AI chips project. “Does all this seem crazy? Pinch yourself; it’s the new normal,” writes Tyler Cowen. Somewhere, the voice of Steve Carell can be heard crying memetically, “It’s a bubble!” But everything is bigger in America, including our capital markets. As for the circular deals, they may also be par for the course.

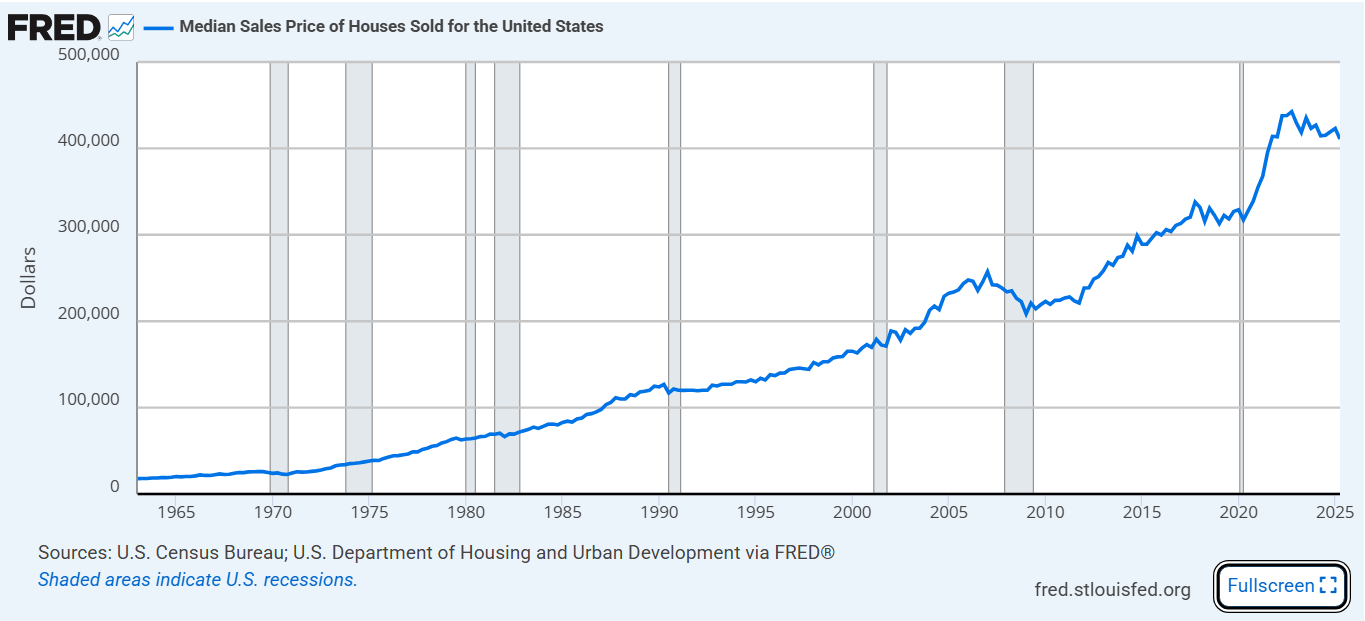

Say what you want about the poor risk management of subprime mortgages in the run-up to the Global Financial Crisis, when Burry made his name one for the history books. Nearly two decades hence, we can probably say that there was no nationwide “housing bubble,” even if that’s what the casual viewer of financial cinema might assume. As ever, Federal Reserve Economic Data (FRED, affectionately) has the chart. It is remarkably non-bubbly.

This is something of a revisionist claim, to be clear. But sometimes the economic-historiographical record needs correction. “Credit should go to Kevin Erdmann,” writes Scott Sumner, “who produced a mountain of evidence against the bubble hypothesis in two very impressive books on housing.” Moreover, “His view, which was once highly contrarian, has now been completely vindicated.” Erdmann has shown in his research that whatever did exist in terms of a housing bubble was concentrated in California, Nevada, Arizona, Florida, and the northeast coast — the places featured in The Big Short. But there probably was no general, nationwide housing supply overhang.

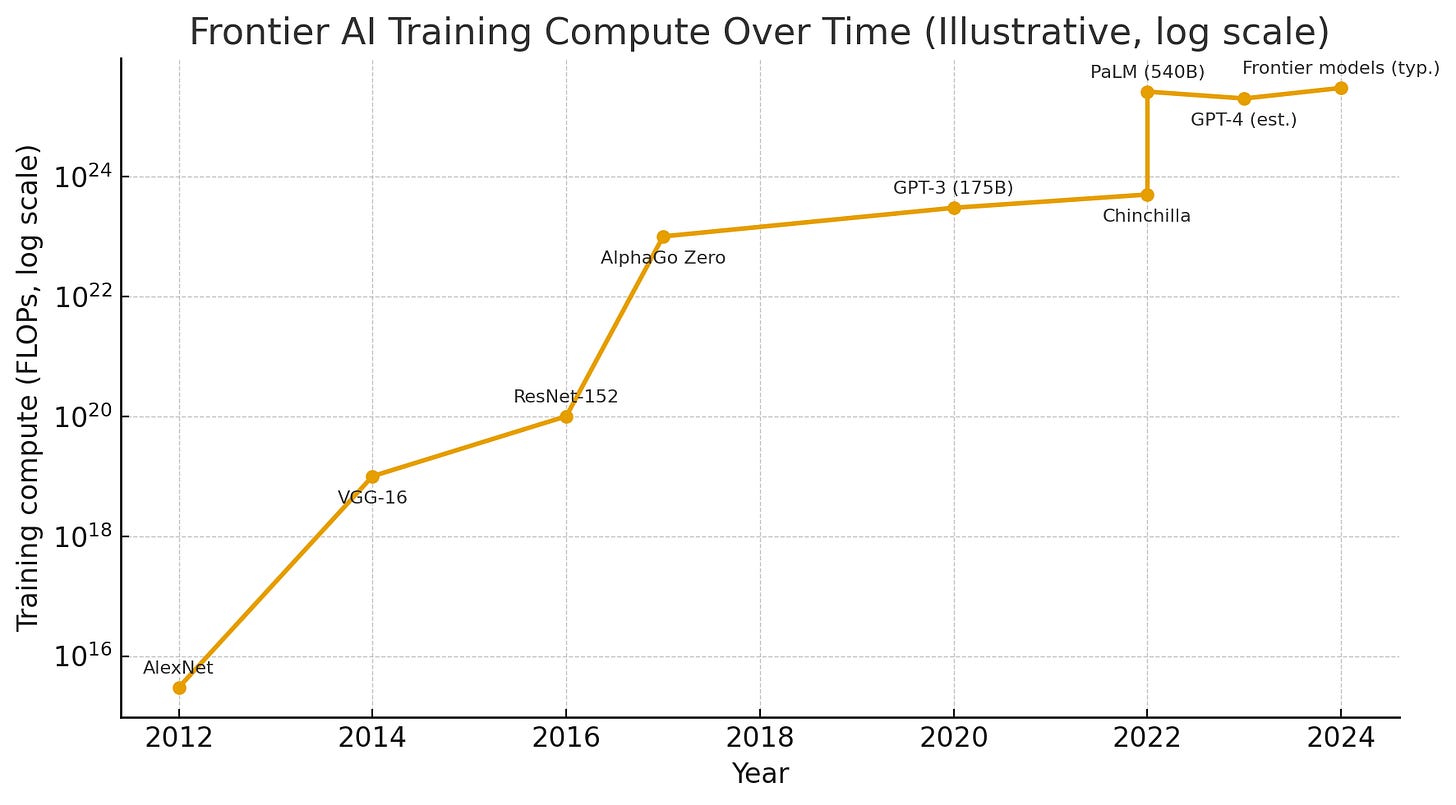

Readers of Byrne Hobart and Tobias Huber’s Boom: Bubbles and the End of Stagnation will be familiar with the dynamic whereby frothy initial investment precedes more stable long-run growth. Technological revolutions test the limits of standard models and paradigms, but the initial frenzy heralds a new era of investment and diffusion — for railroads, the internet, and now likely AI. “The dot-com bubble looked like the peak of delusion,” writes Peter Thiel, “but the truly deluded were those who wanted to indefinitely defer the future.” Looking at the growth in training compute for AI models over the last decade, you might see a similar dynamic emerging.

Scion Asset Management is betting against some of the perceived excesses of AI — firms that don’t live up to the standards of investors like Burry, who follows Benjamin Graham, the “father of value investing.” Other, often larger financial actors are taking the other side of the bet as venture capital firms and new hedge funds like Leopold Aschenbrenner’s Situational Awareness pursue the ”AGI investment thesis.” Both antagonist and protagonist investors make the market hum, and neither guarantees the success or failure of a new industrial revolution.

Far from just being permanent Cassandras who look askance at every “hype cycle,” hedge funds like Scion Asset Management help keep the techno-financial ecosystem healthy by keeping it honest. This happens even when the investors like Burry get it wrong. They put their skin in the game and stake their reputations and their capital on getting it right… or wrong.

This dynamic allows smaller firms like hedge funds to take on more risk without jeopardizing the whole system. The financial historian Sebastian Mallaby, author of the definitive hedge fund history, More Money Than God, is worth quoting in full:

Between 2000 and 2009, a total of about five thousand hedge funds went out of business, and not a single one required a taxpayer bailout. Because they mark all their assets to market and live in constant fear of margin calls from their brokers, hedge funds generally monitor risk better and recognize setbacks faster than rivals: If they take a severe hit, they tend to liquidate and close shop before there are secondary effects for the financial system… The chief policy prescription suggested by the history of the industry can be boiled down to two words: Don’t regulate.

Back to Burry — there is nothing more American than the Yankee underdog who uses his wits to stick it to the elite and the aloof. We’ve had it since the earliest days of our commercial republic. The Washingtonian dramaturge Buff Huntley describes this early American archetype as “an almost surrealistic mixture of naivete and cunning” who “always got the better in a bargain or a swap, but was childishly innocent in the matters of fashion, language, and politics.” Moreover, “his clothes were peculiar.”

Earlier, I called The Big Short “unfortunate” because most people come away from this immensely entertaining movie with a simple fable about smart underdogs beating arrogant bullies. There was a housing bubble, inflated by greed, but a scrappy group of skeptical investors saw through the noise and made bets against the house of cards, which came crashing down in spectacular fashion. “Greed is good,” but Schadenfreude is even better.

Best of all, however, is to look at the long run in financial and technological history and to bet on competitive, sporadic growth.