Sporadic Growth

AI development and organismic cycles

Many are asking whether AI development is becoming a kind of “bubble.” With $100 billion investment pledges and 10-gigawatt data centers in discussion, asking about too much frothiness is a natural question, even if it is impossible to resolve ex ante.

The rapid economic growth of AI raises corollary questions about the political and organizational growth of AI. Managing destabilizing abundance is the core concern of the new research program known as AI benefits sharing. What happens after frontier AI labs create artificial general intelligence (AGI)? Will these firms become too powerful? If they fulfill their ambitions, how can we better redistribute the fruits of their success? What happens to the “social contract” when we reach AGI?

These questions are sometimes phrased in a way that assumes an ongoing centralization of firms, states, and compute, a process that many believe could generate superintelligence at the micro or macro scale. But how confident should we be in that indefinite scaling of socio-technical systems? Over what time horizon?

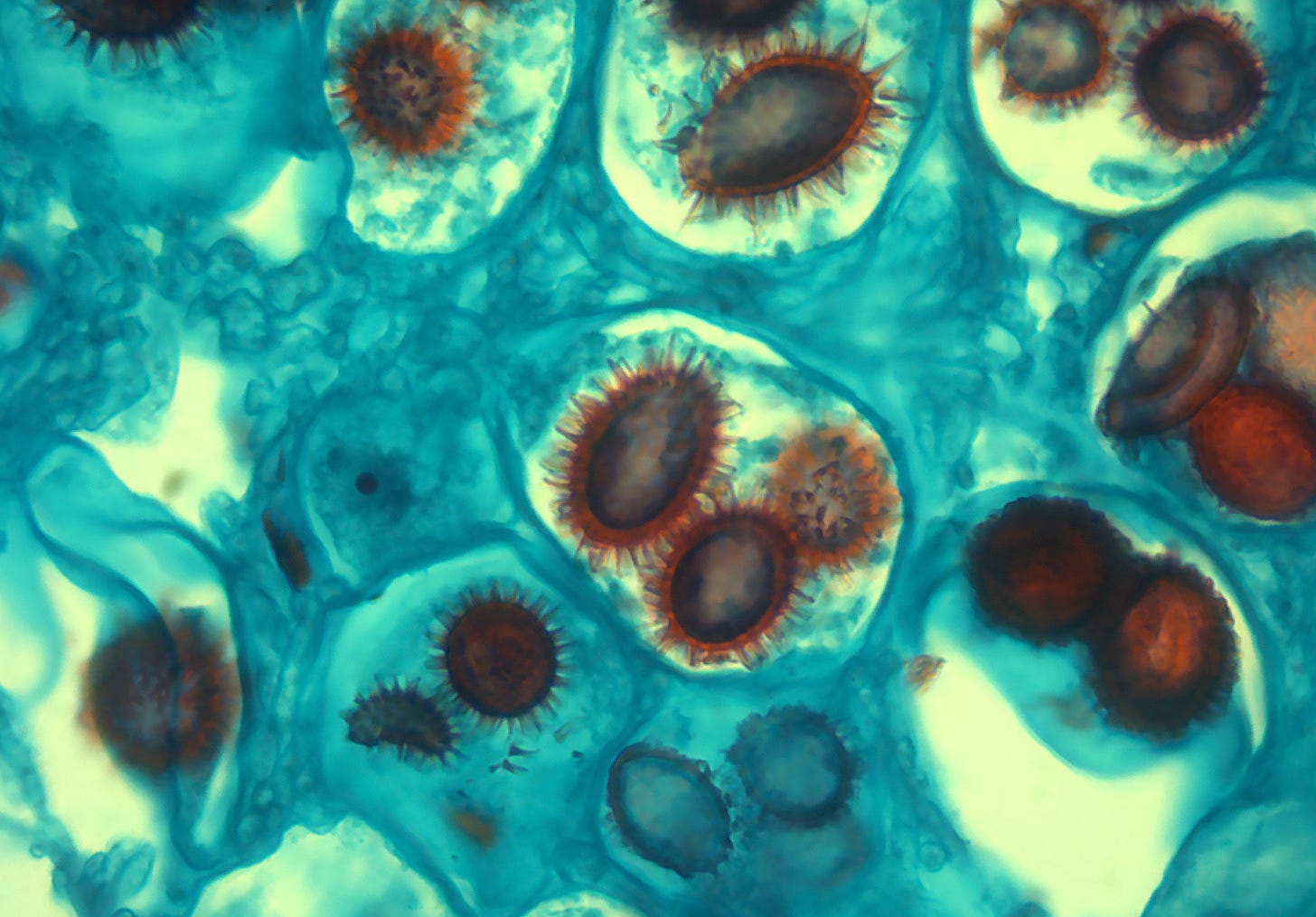

We should be asking whether AI development might be a “spore” — a political phenomenon that grows, bursts, and diffuses as a result of its own competitive pressures.

This is the analogy used by the 20th-century political theorist Bertrand de Jouvenel, who used the term to describe the cycles of political integration and disintegration he saw throughout his reading of the historical record. You can find this short passage in his gloomy 1945 book, On Power: Its Nature and the History of Its Growth, a strange, fractal, often mesmerizing account of the origins and anthropology of the modern state.

Reflecting on elite conflict in imperial Rome, de Jouvenel writes:

[T]he state will in the end be dismembered by the statocracy which it itself has borne. The beneficiaries of the state leave it, taking with them a veritable dowry of wealth and authority, leaving the state impoverished and powerless. Then it becomes the turn of the state to break down these new social molecules, containing as they do the human energies which it needs. And so the process of the state’s expansion starts all over again.

De Jouvenel was arguing for a recurring dynamic in political history. States expand until they can no longer bear their own weight. They disintegrate into new units, which begin the process again in an organismic cycle of life and death. He continues:

Such is the spectacle which history presents to us. Now we see an aggressive state pulling down what other authorities have built up, now we see an omnipotent and distended state bursting like a ripe spore and releasing from its midst a new feudalism which robs it of its substance. [Emphasis mine.]

Centralization scales until it can go no further, then it risks fragmenting. When it ends, its former parts embed and begin again. Each successive spore may be larger or smaller than the last, but the pattern is robust.

De Jouvenel was a journalist, philosopher, and political economist with a “worm’s-eye view” of totalitarianism. He was intimately familiar with the distended spore of Nazism, a force that went from near-total European conquest to abject defeat in less than half a decade. His political identity was fluid, but he is best placed in the French “conservative liberal” tradition that includes writers like Alexis de Tocqueville and Raymond Aron. During the Occupation of France, he supplied intelligence to the British before escaping the Gestapo and finding refuge in Swiss exile. That is where he wrote On Power, digging up the deep roots from which the chaos and horrors of mid-century Europe sprang.

This is not to say that every political organization must naturally build toward totalitarianism or that AI development bears that mark. Rather, my claim is that centralization of power breeds second-order effects — rigidity, internecine conflict, complacency — that gradually overload the initial frame on which it was built. The greater the success, the more others are drawn to it — to participate, plunder, and protest.

We do not need arcane models of human behavior to show us that dynamic, and we should assume it will replicate in the future with new firms and varieties of cognition. In her essay on voluntary and market-based approaches to AI benefits sharing, Elsie Jang writes:

[I]f, as many technologists believe, transformative AI lies on the near horizon, then our real deficit is not technical foresight but social, political, and economic imagination.

I think de Jouvenel would endorse that claim. Analyzing technological and economic futures is extraordinarily difficult, but cultivating the moral imagination needed to navigate uncertainty is more difficult still. De Jouvenel devoted the last part of his career to working on the moral and epistemic conditions of political forecasting. This included working with the RAND Corporation and contributing to futurological research in tandem with Olaf Helmer, Walter Cronkite, Herman Kahn, Isaac Asimov, and others — covered in a 1967 short documentary, The Futurists.

We can easily discount core lessons of political economy that are likely to remain just as applicable post-AGI. “Maybe this time is different?” Regardless of the scale of change, many of the core dynamics inherent in living systems and human nature — cooperation and competition among strategic, self-interested agents in a world intrinsically marked by scarcity — will persist. Navigating this requires a robust moral imagination — the essential point de Jouvenel makes in his interview (below). “I don’t want to know how things are to be, I want to exert action… so that [things that should be] have more chances of being.”

We live without knowing when investment bubbles and organizational spores will burst and exactly what will grow in their place. Anton Leicht is worth quoting on this point:

I feel like many colleagues working on frontier AI policy dismiss “bubble talk” very quickly. But I think that’s short-sighted: there can be a bubble on top of a very real phenomenon. And because talk affects public perception, which in turn affects political support, and then spending decisions, mere “talk” of a bubble can very easily manifest radical market corrections.

The dynamics generated by bubbles and spores can lead to strange feedback loops, dynamic systems with opaque emergent properties.

Central to the problem of valuation is deep uncertainty about the short- and long-run effects of artificial general intelligence. We’re still debating the scale of tech shocks centuries after they occur. Political and economic judgments beyond a five-year time horizon are hard enough when the clouds have dispersed, let alone in the middle of a downburst. Financiers and technologists in AI now work at the “epistemological frontier,” a term used by the historian William Deringer to describe the borderlands of constructivism, where “rationality has reached its limits.”

That is not to cast doubt on the technological possibilities of AI, but rather to remind us that epistemic and moral humility are deeply intertwined. Whatever you imagine, do not think we will be arriving at a form of stasis that will lend itself to rational management, free from uncertainty and detached from history.

The AI benefits discussion should reflect that entanglement — and we should consider the spore.